Introduction: Albinism — a Global and Underestimated Issue

A bright sunny day. Stepping outside at such a moment, a person instinctively squints, looks for shade, or throws something over their shoulders. This is how the human body seeks protection. Part of this protection is already built into our skin and eyes — melanin, an evolutionary defense against the sun. This natural pigment acts as a protective screen, absorbing and dispersing the aggressive energy of ultraviolet radiation.

For hundreds of thousands of people with albinism around the world, this basic protective mechanism works differently. Their skin and eyes contain very little melanin or none at all. According to international organizations, albinism occurs on average in one out of 17,000–20,000 people. However, in some regions of Africa this number is significantly higher — up to one in 1,000–4,000 individuals. Behind these figures are real human lives, for whom an ordinary sunny day can pose a serious threat.

In sub-Saharan Africa, where solar radiation is especially intense, the lack of natural protection leads to very early and severe skin damage, including skin cancer. Tragically, skin cancer remains the leading cause of premature death among people with albinism in these regions. Many children with albinism already show pronounced signs of chronic sun damage by the age of 8–10. These are not rare exceptions — this is a systemic problem.

In Europe and other regions with less aggressive sunlight, despite better access to medical care and information about albinism, the risks are also often underestimated. The sun is perceived as mild and harmless. However, repeated sunburns in childhood, irregular use of sun protection, and the belief that “burning isn’t possible” lead to the same consequences — they simply develop more slowly and become apparent later in life.

Yet, in most cases, the severe skin complications associated with albinism are preventable. And this path begins with awareness.

What Is Albinism Really?

Albinism is not a disease. It is a genetic condition a person is born with. It occurs due to changes in genes responsible for the production of melanin—the very pigment that gives color to the skin, hair, and eyes. In simple terms, in the body of a person with albinism, the “instructions” for producing this pigment are written differently, resulting in very little melanin being produced, or none at all. As a result, medical care focuses not on finding a “cure,” but on proper management and prevention of associated risks.

Most often, albinism is inherited in what is known as a recessive pattern. This means that for the condition to manifest, a child must inherit the altered gene from both parents. The parents themselves, having one altered and one typical copy of the gene, usually show no visible signs and often do not know they are carriers. These genetic changes disrupt the complex process of melanin production in the skin.

A lack of melanin determines all the key features of albinism, primarily affecting the skin and vision.

Skin manifestations. Skin without the protective melanin filter absorbs almost all ultraviolet radiation. This results not only in very light skin and hair, but also in extreme vulnerability. Even short periods of sun exposure can cause redness and sunburn. Long-term, cumulative sun exposure over the years leads to premature skin aging and damages cellular DNA, which directly increases the risk of developing skin cancer.

Ophthalmological manifestations. Melanin is essential for proper eye development and clear vision. Its deficiency leads to a number of characteristic changes: very light, often semi-transparent irises; high sensitivity to light (photophobia); and reduced visual acuity. It is important to emphasize that these changes affect only the visual system and have no impact on a person’s intelligence or cognitive abilities.

Schoolgirl with albinism experiencing vision difficulties due to reduced melanin in the eyes.

Proper eye care and protective glasses can help schoolchildren with albinism manage vision challenges.

Any discussion of albinism must also address and dispel dangerous myths that contribute to stigma:

- It is not contagious: albinism cannot be “caught.” It is a genetic trait and is not transmitted through touch, shared utensils, or the air.

- It does not affect intelligence: visual impairment may require adapted learning materials or conditions, but it has no connection to a person’s intellectual potential.

- It is not magic: superstitions that attribute magical or supernatural properties to people with albinism—particularly widespread in some regions of Africa—are dangerous misconceptions with no scientific basis.

From a medical perspective, albinism is therefore primarily a condition of increased vulnerability of the skin and eyes to environmental factors, especially solar radiation. Understanding this simple but fundamental idea is the first and essential step toward building an effective system of health protection.

The Sun and Ultraviolet Radiation: The Primary Risk Factors

Sunlight as perceived by the human eye represents only a small portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. The invisible yet biologically most active component consists of ultraviolet (UV) radiation. To understand the risks associated with albinism, it is essential to distinguish between the two main types of UV radiation that reach the Earth’s surface: UVB and UVA.

UVB rays (280–315 nm) are high-energy rays. They primarily affect the outer layer of the skin—the epidermis—and are the main cause of sunburn (redness, erythema) and direct DNA damage to skin cells. This type of radiation is considered the primary initiator of skin cancer development.

UVA rays (315–400 nm) penetrate deeper into the skin, reaching the dermis. Although they are less energetic, they are present in sunlight year-round at relatively constant intensity and can pass through clouds and window glass. UVA radiation is the main contributor to premature skin photoaging (the formation of deep wrinkles and loss of elasticity) and also plays a role in carcinogenesis by enhancing the damaging effects of UVB.

Skin with a normal amount of melanin has a multilayered defense system. Melanin in the epidermis absorbs and scatters up to 70–80% of UV radiation, functioning as a built-in natural sunscreen. In addition, in response to UV exposure, the skin initiates tanning (increased melanin production) and thickening of the stratum corneum—adaptive, though limited, protective mechanisms.

Sun-safe habits: hats help children with albinism reduce UV exposure.

In albinism, this system is absent. UV radiation, especially UVB, penetrates the skin layers almost unhindered. Each exposure results in extensive DNA damage to keratinocytes, the primary cells of the epidermis. While healthy cells possess DNA repair mechanisms, in albinism the scale of damage often exceeds the capacity of these systems.

Unrepaired errors in the genetic code accumulate over time. This cumulative effect is key: damage acquired in childhood and adolescence adds up with each subsequent sun exposure. Years later, these accumulated mutations may trigger uncontrolled cell division, leading first to precancerous changes and eventually to malignant disease.

It is important to understand that risk is not created solely by direct, intense sunlight. Diffuse radiation on cloudy days, reflected radiation from water, sand, concrete, or snow (which can increase total UV exposure by 50–90%), and even radiation passing through light clothing or filtered by tree shade all contribute to the cumulative dose. Therefore, a protective approach must be comprehensive and consistent, not occasional or situational.

Statistics: Shared Challenges and Regional Tragedies

The prevalence of albinism varies across different regions of the world. On a global scale, it is estimated at approximately one case per 17,000–20,000 people. However, this average figure conceals significant geographic differences driven by population genetics.

In Europe and North America, prevalence is estimated at around 1:17,000–1:20,000. In Africa, particularly in sub-Saharan regions, the rates are significantly higher. For example, in Tanzania and parts of East Africa, prevalence is estimated at 1:1,400–1:5,000, making albinism a relatively common condition in these areas. This high frequency is explained by genetic characteristics of isolated populations and, in some cases, by cultural practices that contribute to the persistence and transmission of the relevant genes.

Data collected by international and local NGOs, as well as medical missions, paint a deeply concerning picture. In African countries with high levels of solar radiation, skin cancer is the leading cause of premature death among people with albinism.

The numbers are stark. According to Under the Same Sun, more than 80% of people with albinism in Tanzania do not live beyond the age of 40, with the majority of these deaths linked to advanced skin cancer. The risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) for a person with albinism living in equatorial Africa is thousands of times higher than that of an average individual with normal melanin levels. Moreover, the average age at diagnosis of malignant skin tumors in Africa often falls in the second or third decade of life, whereas in European populations without albinism this peak typically occurs after the age of 60.

This catastrophic disparity is not driven by the biology of albinism itself, but by a convergence of factors:

- Extremely high levels of UV radiation

- Lack of accessible and affordable protective measures (sunscreen, protective clothing)

- Socioeconomic barriers, including poverty, stigma, and limited access to medical care

- Low awareness of risks and prevention methods among both the general population and primary healthcare providers

In Europe and other developed regions, access to protective measures, regular dermatological care, and early diagnosis is significantly better. This allows the onset of skin cancer to be delayed and mortality to be substantially reduced. However, risk underestimation and inconsistent protection mean that people with albinism in these regions still face actinic keratosis and skin cancer at a younger age than the general population—though later than their peers in Africa. These statistics clearly demonstrate that albinism is not only a medical issue but also a deeply social one, and that addressing it requires a comprehensive, systemic approach.

Africa: When Skin Damage Begins in Childhood

In sub-Saharan African countries such as Tanzania, Mozambique, Kenya, and Malawi, the dermatological reality for people with albinism follows a tragically predictable course, driven by the combination of extreme ultraviolet radiation and limited access to protective resources. The clinical picture develops rapidly, often beginning in early childhood. As early as 5–7 years of age, persistent erythema (redness), dryness, scaling, and the appearance of early lentigines and solar freckles can be observed on the most exposed areas of the skin—the face, ears, neck, forearms, and lower legs—instead of healthy skin. These changes are not cosmetic imperfections, but visible markers of cumulative photodamage.

Ana, a representative of Kanimambo, teaches a mother how to protect her children with albinism from the sun.

Dermatology team giving hats and guidance on full sun protection.

By adolescence, approximately between the ages of 12 and 15, most patients develop the classic presentation of chronic actinic damage. The skin becomes coarse and thickened, marked by areas of atrophy and hyperkeratosis. At this stage, multiple foci of actinic keratosis are commonly identified—rough, often pigmented (ranging from pink to brown) papules or plaques that are firmly adherent to the skin surface. Their appearance marks the transition to a precancerous state, in which the proliferation of keratinocytes with damaged DNA becomes uncontrolled, although not yet overtly destructive or malignant.

Without medical intervention or regular monitoring, the progression of the pathological process in the skin is almost inevitable. Active actinic keratoses, particularly those subjected to repeated mechanical trauma, transform into squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). In the African context, this type of cancer in individuals with albinism is characterized by aggressive behavior: rapid ulceration, infiltration of underlying tissues, and—most dangerously—metastasis to regional lymph nodes.

Due to delayed access to medical care, when tumors have already reached significant size, the options for radical surgical treatment are often limited. According to epidemiological studies, up to 90% of people with albinism in East Africa die from complications of advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the skin before the age of 40. These figures underscore that, in this context, cancer is not a fatal coincidence but a direct consequence of the absence of systematic prevention, early diagnosis, and accessible treatment.

Europe: Different Conditions and Underestimated Risks

In Europe and other regions with a temperate climate, the clinical course follows a similar pathogenic pathway, but unfolds over a much longer time frame. Lower overall UV intensity, a cooler climate, and generally better access to sun protection create an illusion of manageable risk. Paradoxically, this illusion becomes the key factor behind delayed complications.

The primary threat here is not constant extreme sun exposure, but episodic, high-intensity UV exposure that is often perceived as insignificant. This includes sunburns acquired during summer vacations, picnics, outdoor sports without adequate protection, as well as travel to regions with high solar radiation—seaside resorts or ski areas, where reflection from water or snow significantly amplifies UV exposure.

The cumulative effect of these episodes manifests not in adolescence, but in the second or third decade of life and beyond. Adults with albinism in Europe are diagnosed more frequently than the general population with actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, and, to a lesser extent, squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. However, detection often occurs at later stages than would be optimal.

The underlying reason lies in a false sense of security and the lack of routine practices for regular self-examination and professional dermatological screening. Many patients—and even some primary care providers—mistakenly believe that the risk of skin cancer in albinism under European conditions is minimal. As a result, medical consultation often occurs only when tumors ulcerate or when long-standing, enlarging lesions—ignored due to the absence of pain—become impossible to overlook.

Thus, the European context shifts the problem from an extreme and obvious threat to a hidden, chronic one—particularly insidious because it is persistently underestimated.

Actinic Keratosis: The Point Where Progression Can Still Be Stopped

The evolution of sun-induced skin damage in albinism does not occur abruptly, jumping from healthy tissue directly to malignant tumor. Between these states lies a clearly defined clinical and histological stage—actinic (solar) keratosis. This condition is rightly considered an obligate precancer, meaning it carries a high likelihood of progression to invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Its pathophysiological basis lies in irreversible UV-induced mutations in the basal layer keratinocytes of the epidermis. These altered cells begin to proliferate uncontrollably, forming areas of atypia that remain confined to the epidermis without invading the dermis. This is the critical “border zone.”

Clinically, actinic keratosis in individuals with albinism often presents not as a solitary lesion, but as multiple foci against a background of chronic photodamage. Its appearance can vary significantly, necessitating careful examination. Most commonly, lesions appear as rough, sandpaper-like spots or small plaques that are easier to feel than to see. Their color ranges from subtle pink or skin-toned to pronounced red or yellowish-brown. The surface may be dry, scaly, or covered with a firmly adherent crust that reforms after shedding. Lesions may begin at the size of a pinhead and enlarge to several centimeters in diameter.

Typical locations include areas of maximal sun exposure: the forehead, nose, cheekbones, ears, receding hairlines on the scalp, the back of the neck, forearms, and the backs of the hands.

The critical importance of this stage lies in the fact that the process remains manageable. At the level of actinic keratosis, progression to invasive cancer can be prevented in most cases. Effective and minimally invasive treatment options are available, including cryotherapy (liquid nitrogen), photodynamic therapy, and topical treatments such as diclofenac, fluorouracil, or imiquimod-based creams. However, the success of any intervention depends directly on timely detection.

The appearance of any persistent, rough, intermittently inflamed, or scaling lesions on the skin is a direct signal for immediate dermatological consultation. Ignoring these early warning signs allows atypical cells to continue their evolution, accumulating further mutations that ultimately confer the ability for invasive malignant growth.

Squamous Cell and Basal Cell Skin Cancer: Features in Albinism

When the intensity of skin changes progresses and repair mechanisms can no longer cope with DNA damage, cells with malignant potential emerge. Control over their division and growth is lost, forming an invasive malignant tumor capable of affecting not only all layers of the skin but also spreading throughout the body (metastasis).

The two main types of non-melanoma skin cancer affecting people with albinism are squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Their biological behavior, clinical presentation, and prognosis differ significantly, which is essential for early diagnosis.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) poses the greatest oncological threat, especially in areas with high sun exposure. It develops from keratinocytes in the spinous layer of the epidermis and often represents a logical progression from untreated actinic keratosis.

SCC is relatively aggressive. Clinically, it may begin as a firm nodule or, more commonly, as a long-standing non-healing erosion or ulcer with raised, rolled edges and a crusted or bleeding base. The tumor grows rapidly, infiltrates underlying tissues (subcutaneous fat, ear or nasal cartilage, muscles), and has a significant metastatic potential—spreading via lymphatic vessels to regional lymph nodes, and in advanced cases, to distant organs. SCC accounts for the overwhelming majority of fatal skin cancer cases in people with albinism in Africa.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC), arising from basal layer cells, is less aggressive. It grows slowly, often over years, and rarely metastasizes. However, this does not make it harmless. Without treatment, BCC is locally destructive: like corrosion, it gradually destroys surrounding tissues—skin, subcutaneous tissue, cartilage, and bone.

Clinically, BCC may appear as a translucent “pearly” papule with telangiectasia (visible surface blood vessels), sometimes ulcerating at the center to form a chronic non-healing sore. Other BCC forms may appear as flat, firm, scar-like whitish patches with indistinct borders, often leading to delayed diagnosis.

In people with albinism, both types of skin cancer share a critical feature: they almost always develop against a background of pronounced chronic photodamage, which can mask early signs among numerous other lesions (keratoses, erythema, hyperpigmentation). Additionally, early stages are usually painless. The absence of pain combined with the familiar appearance of damaged skin is the main reason patients delay seeking medical attention, allowing the disease to progress to dangerous stages.

Why Early Detection Changes Everything

The gap between the appearance of early malignant changes and the time of diagnosis is often tragically wide. This delay is caused by multiple interconnected factors, which can be described as a triad of misconceptions.

The first and most insidious factor is the absence of pain at early stages. Both actinic keratosis and early forms of SCC and BCC develop painlessly. Itching, discomfort, or tenderness appear only after ulceration, infection, or deep tumor invasion—that is, at advanced stages. Without physical warning signs, individuals naturally delay consulting a doctor, attributing changes to “normal dryness,” “irritation,” or minor injury.

The second element is a lack of oncological vigilance—both by patients and their families, and, in some cases, by primary care providers. In contexts where chronic skin damage from childhood is perceived as inevitable in albinism, new nodules or non-healing crusts may not be recognized as potentially dangerous. A culture of routine preventive skin checks, especially in resource-limited regions, is not established. In Europe, the risks are often systemically underestimated, also leading to missed opportunities.

The third key factor is the absence of systematic professional monitoring. Even with vigilance, without regular (at least annual) dermatological exams by a specialist familiar with albinism, early detection is difficult. Patients may simply fail to notice a slowly growing nodule on the back or changes in the character of an old lesion. Only a trained dermatologist using dermoscopy can distinguish early BCC from benign keratoses or detect signs of malignant transformation in actinic lesions.

The difference between early and late detection is fundamental. Early diagnosis, when the tumor is confined to the epidermis or superficial dermis, allows minimally invasive treatments with high effectiveness and complete cure: surgical excision with minimal healthy tissue removal, cryotherapy, laser ablation, or photodynamic therapy. In contrast, late diagnosis, when SCC has deeply invaded, ulcerated, and metastasized, requires complex, multi-stage, often disfiguring surgery with possible plastic reconstruction and adjuvant radiotherapy, with an uncertain prognosis. Overcoming this triad of misconceptions through education and systematic monitoring is a critical step in preserving health and life.

Everyday Sun Protection: Not Heroism, but Habit

The most effective strategy to reduce cancer risk in albinism lies not in complex treatments but in consistent, well-structured, and integrated daily prevention. The goal is not to impose restrictions, but to create a conscious lifestyle where sun protection becomes as natural and routine as brushing teeth. This approach shifts the focus from treating consequences to managing causes.

Prevention is based on a set of measures known as “sun hygiene.” The principles are universal but require uncompromising adherence in albinism. This includes planning daily activities according to sun intensity, preferring shaded routes, wearing protective clothing and hats, and daily use of sunscreen. Effectiveness depends on understanding the logic behind each measure. For example, lightweight yet dense dark clothing made of fabrics with UPF filters physically blocks rays and reduces the need to constantly reapply sunscreen on covered areas, making protection more reliable and less burdensome.

Nuno presenting Kanimambo programs in Maputo, with Clarins,

key donation partner.

Skin care is another crucial element, aimed at maintaining barrier function and minimizing the impact of inevitable minimal sun exposure. Daily routines should include gentle cleansing with products free from harsh surfactants and alcohol, and intensive hydration. Creams and lotions containing ceramides, hyaluronic acid, urea, panthenol, and niacinamide help restore the skin barrier, enhance resistance to environmental stressors, and support repair.

Cosmetic procedures must be approached with caution. Aggressive treatments—deep peels, laser resurfacing, dermabrasion—are contraindicated due to chronic photodamage and high neoplasia risk. Only gentle, restorative procedures are permissible, such as superficial chemical peels with lactic or mandelic acid under strict dermatological supervision.

Special attention is required for coexisting conditions. For instance, in albinism with atopic dermatitis, where barrier function is already compromised, sun protection should use products for sensitive skin (physical filters, fragrance-free), and basic care should include therapeutic products to control inflammation. For diagnosed actinic keratosis, skin care becomes part of the medical protocol: after lesion removal, strict photoprotection and dermatologist-recommended topical agents help prevent recurrence and control keratinocyte proliferation.

SPF, Clothing, and Sunglasses – How They Work in Real Life

Effective sun protection relies on three physical principles: reflection, absorption, and blocking of radiation. Protective measures—clothing, creams, and sunglasses—use these principles differently, and understanding their mechanisms ensures maximum benefit.

Clothing is the first and often most reliable line of defense. Its effectiveness depends not only on sleeve length but on fabric characteristics: weave density, thread thickness, color, and crucially, the presence of an ultraviolet protection factor (UPF). Dark or bright dense polyester or nylon blocks more rays than a light cotton shirt.

Clothing with UPF 30+ (meaning only 1/30 of UV rays reach the skin) provides predictable, continuous protection, unaffected by sweat and requiring no reapplication. A wide-brimmed hat (7–10 cm) shades the face, ears, and back of the neck—the most vulnerable areas for actinic keratosis and skin cancer. Relying on ordinary summer clothing is a common mistake; wet or stretched fabrics can drop UPF below 10, which is clearly insufficient.

Sunscreens (SPF) act as chemical or physical screens on the skin surface. SPF (Sun Protection Factor) mainly measures protection against UVB rays, which cause burns. SPF 30 theoretically increases the time it takes for skin to redden by 30 times, but only if applied correctly. Most people apply 2–4 times less than recommended (2 mg/cm²; ~36 g for the whole body). Sunscreen should be applied 15–20 minutes before sun exposure and reapplied every 2 hours, and after swimming or sweating. Products should offer broad-spectrum protection (UVA/UVB) with SPF 30–50+, with mineral filters (titanium dioxide or zinc oxide) preferred for sensitive skin. Sunscreen is a necessary complement, not a replacement for shade or protective clothing.

Sunglasses serve both comfort and preventive medical functions in albinism. They must block 99–100% of UVA and UVB, verified by labeling. Quality lenses prevent further eye photodamage and reduce photophobia. Large lenses or wraparound frames prevent side-entry of rays. Any stigma associated with wearing dark glasses must be overcome—they are medical devices, not accessories.

Ultraviolet Index: Why Tracking Numbers Matters

UV intensity at the Earth’s surface is neither constant nor obvious. It depends on many factors: sun elevation (time of day and season), latitude, altitude, cloud cover, ozone layer, and reflective surfaces (water, sand, snow). Human perception—heat or brightness—is unreliable, as warmth comes mainly from infrared and brightness from visible light. One can feel cool on a cloudy, windy day while still receiving enough UV exposure to damage unprotected skin.

To objectively assess risk, the World Health Organization (WHO) and other agencies developed the Ultraviolet Index (UVI), a standardized 1–11+ scale indicating potential sun hazard at a given time and place. UVI data are widely published in weather forecasts, apps, and meteorological websites.

Index interpretation and actions:

- UVI 1–2 (Low): Minimal risk. Protection needed only for very fair skin.

- UVI 3–5 (Moderate): Medium risk. Stay in shade at midday, wear a hat and sunglasses, apply sunscreen.

- UVI 6–7 (High): High risk. Enhanced protection needed: limit sun exposure 10:00–16:00, wear protective clothing, apply sunscreen.

- UVI 8–10 (Very High) / 11+ (Extreme): Very high risk. Unprotected skin can burn in minutes. Stay in shade, wear full protective clothing, hat, sunglasses, and actively use sunscreen.

For people with albinism, monitoring UVI should become routine. Planning walks, travel, sports, or even daily routes to work or school according to forecasted UVI allows proactive risk management. “High-risk” hours are when the sun is high in the sky (~10:00–16:00), but in summer and tropical regions, this interval can be longer. Focusing on UVI numbers rather than personal sensations is a scientific, evidence-based approach that eliminates randomness and underestimation in photoprotection.

Digital Technologies and Skinive: A New Level of Prevention

Modern dermatology is undergoing a digital transformation, where technology becomes an integral tool for both doctors and patients. At the center of this process is artificial intelligence (AI), specifically its branch focused on machine learning for medical image analysis.

Global interest in this field is growing rapidly: the number of scientific publications, AI-based medical devices approved by regulators, and available mobile applications is increasing exponentially. These systems are trained on extensive databases containing hundreds of thousands of images of various dermatological conditions—from acne and eczema to melanoma and basal cell carcinoma. The algorithms learn to recognize complex patterns, often barely perceptible to the naked eye, that are characteristic of specific skin changes.

The primary value of AI in dermatology lies not in replacing the doctor, but in enhancing their capabilities and empowering patients. These technologies serve as a powerful tool for triage and early screening. They can instantly analyze a skin image, highlight potentially dangerous areas that require prompt professional attention, and thus reduce the time from noticing a change to consulting a specialist. For people with albinism living in regions with limited access to dermatologists, such tools can become a critical link in the healthcare system.

Mobile applications like Skinive represent a practical implementation of these technologies, adapted for everyday use. Their functionality goes beyond simple scanning, forming a comprehensive ecosystem for managing photoprotection:

- UV Index Monitoring with Forecasting: Unlike static weather reports, specialized apps integrate a user’s geographic location, time of day, season, and cloud cover to provide personalized, up-to-date information about UV risk now and in the coming days. This allows users to plan outdoor activities, e.g., moving a walk to the morning if extreme UV is expected or preparing full sun protection before traveling to a sunny region.

- Personalized Safe Sun Exposure Timer: A key feature for people with albinism. The algorithm considers a very fair or phototype I skin (typical for albinism), applied sunscreen with its specific SPF, current UV Index, and possibly clothing type, calculating the recommended safe time before potential photodamage. This timer turns abstract advice like “don’t stay in the sun too long” into a concrete, measurable, and understandable guideline, helping develop an intuitive sense of safety.

- Early Skin Change Assessment Using AI Algorithms: Users can document their skin condition regularly, creating a digital skin passport. When a new lesion appears or an existing one changes (papule, plaque, flaking area), the system uses trained neural networks for initial assessment. Importantly, AI does not make a diagnosis; it evaluates risk and highlights changes most likely requiring dermatological consultation (e.g., marked as “needs doctor’s attention” or “high risk”). For someone with multiple actinic keratoses, this helps distinguish typical stable lesions from new, atypical growths—a task difficult even with self-monitoring.

Integrating these functions sets a new prevention standard, shifting from a reactive approach (acting after a problem arises) to a predictive or proactive one. Technology handles routine monitoring of objective risk parameters (UV Index) and provides tools for regular self-observation, turning the patient from a passive observer into an active participant in their skin health.

However, a fundamental principle remains: digital tools are supportive aids for early risk detection, but final diagnosis, clinical decisions, and treatment are the exclusive prerogative of a qualified dermatologist.

Skin Self-Examination: Regularity as a Cornerstone of Early Detection

Despite the importance of technology and professional monitoring, the most accessible and immediate method for skin control remains regular self-examination. Its goal is to detect new or changing lesions that may require professional attention. Effective self-examination depends not on perfect knowledge of every skin cancer type, but on developing a habit of systematic and careful observation.

Optimal frequency: once per month. This interval is sufficient to track noticeable changes, yet not so frequent as to become burdensome. Examine in a well-lit room, using a large mirror, and a second mirror for hard-to-see areas like the back, back of the thighs, and scalp under hair. Inspect the entire body, including between fingers and toes, soles, nail beds, and genitals, as skin cancer, though rare, can occur anywhere.

During examination, look for anything following the “ugly duckling” rule—lesions that differ from others in color, size, shape, or texture. Specific warning signs include:

- New, rapidly growing papules or nodules

- Non-healing sores or ulcers lasting several weeks, sometimes bleeding or crusting

- Any existing patch or plaque that changes borders (becomes asymmetric or irregular), color (darkens, lightens, becomes mottled), size, or elevation

- Subjective sensations like itching, tenderness, or tingling in a long-standing lesion

For people with albinism, whose skin often shows multiple chronic photodamage manifestations (dryness, freckles, atrophic patches), self-examination is more challenging. Maintaining a simple photo archive is helpful: take photos of heavily affected areas (face, forearms, lower legs) every 3–6 months. Comparing current images with previous ones helps objectively detect gradual changes that might escape daily notice. Key: stay calm when spotting a suspicious lesion—document it and schedule a dermatologist consultation.

Contact with a Dermatologist: Building Long-Term Partnerships

Even with diligent self-examination and digital tools, the final word in diagnosis and treatment always belongs to the dermatologist. For a person with albinism, establishing and maintaining contact with a specialist is a strategic task, as important as sun protection itself. This is especially critical in regions with limited access to qualified dermatologists, where every visit requires significant effort and resources.

The ideal model shifts from situational, problem-driven visits to planned, continuous monitoring. The goal is not only to treat existing actinic keratoses or skin cancers but also to prevent them and ensure early detection. From the first consultation, discuss an individual monitoring plan with the doctor, taking into account age, extent of photodamage, geographic conditions, and social factors. This plan may include:

- Recommended frequency of check-ups (e.g., every 6–12 months)

- Dermoscopic mapping of all suspicious nevi and keratoses

- Clear instructions for action if new lesions appear between visits

Where specialist access is limited, primary care doctors, pediatricians, or NGO mobile clinic staff may serve as first contacts. Their awareness of albinism-specific risks is essential. Patients or caregivers must communicate key information: high oncological risk, painless onset of most lesions, and the need for dermatology referral if any doubts arise.

Connecting with local or international organizations supporting people with albinism can assist in finding specialists or arranging telemedicine consultations, bridging the gap between remote patients and experts in major centers.

An optometrist from a Kanimambo partner organization travels from Portugal to fit glasses individually and provide updated prescriptions.

Thus, contact with a dermatologist should be seen as a long-term partnership, aimed at preserving skin health throughout life. An engaged patient who asks questions, discusses monitoring plans, and responsibly follows recommendations significantly enhances the effectiveness of this collaboration, creating a foundation for safety and well-being.

The Role of Global and Regional Communities: Collective Power in Addressing Systemic Challenges

The challenges faced by people with albinism, particularly regarding health and social integration, are often not just individual but systemic. These issues are difficult to tackle alone. This is where the role of community organizations, associations, and international networks becomes essential. By joining forces, they create supportive infrastructures, advocate for legislation, and break down entrenched stereotypes. Their work focuses on several key areas, each directly affecting skin cancer prevention and quality of life.

Legal protection and anti-stigma efforts form the foundation. In many countries, especially in Africa, people with albinism face discrimination, violence, and social isolation due to deeply rooted mystical beliefs. Organizations conduct continuous educational campaigns with local communities, opinion leaders, and media, explaining the genetic nature of albinism. They also advocate for laws criminalizing violence and discrimination, ensuring human rights are upheld. Without basic physical safety and social acceptance, any medical programs are limited in effectiveness.

Access to protective resources provides direct, life-saving support. In regions with low income levels, where specialized sunscreens and protective clothing are unavailable or unaffordable, NGOs become critical distribution channels. They organize the supply of high-SPF creams, wide-brimmed hats, UV-filter sunglasses, and protective clothing. Importantly, this is not just a one-time humanitarian shipment, but the development of sustainable local programs, training in proper use, and, when possible, establishing local production to reduce costs.

Medical support and knowledge sharing are another critical area. Many organizations organize medical missions where dermatologists and surgeons perform skin exams, cryotherapy for actinic keratoses, tumor removal surgeries, and train local healthcare workers. They also create educational materials in local languages—brochures, posters, and videos—on photoprotection and self-examination.

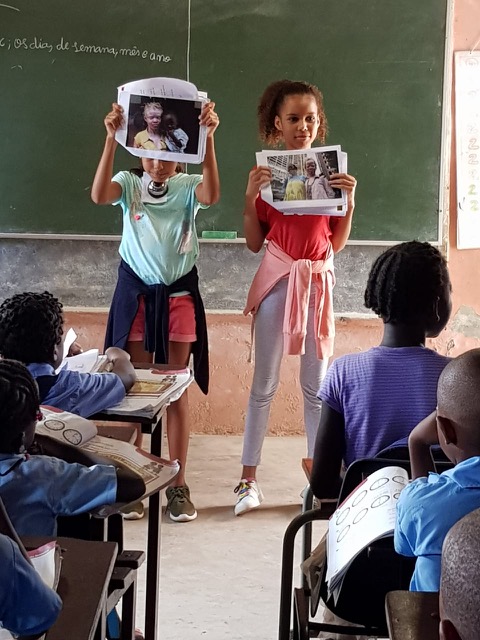

A particularly impactful example is Kanimambo – Association for the Support of Albinism, active in Mozambique since 2012. Kanimambo places education at the heart of its mission, recognizing it as the most powerful and lasting form of protection for people with albinism. Through continuous community awareness initiatives, training of teachers and caregivers, and broad educational programs, the association builds a foundation of understanding and safety, because meaningful protection begins with knowledge and informed daily practices. Alongside education, Kanimambo provides essential preventive resources such as high-SPF sunscreens, healing creams, prescription eyeglasses, UV-protective sunglasses, and wide-brimmed hats, while conducting regular ophthalmology missions and supporting social and professional integration. Its collaboration with Skinive strengthens this mission by making reliable guidance and early-risk identification tools more accessible, reinforcing the shared goal of reducing preventable mortality and helping individuals with albinism live safely and confidently in the sun.

Networks like the Africa Albinism Network serve as platforms for sharing best practices across the continent, amplifying collective impact. South African ALBINISM SA works on advocacy, education, and provision of sun protection products. Russian-language project Mila for Africa Kenya emphasizes direct medical and humanitarian aid, supplying sunscreens and organizing safe spaces in schools.

These and many other groups form a global support ecosystem that not only saves lives today but also works toward a world where people with albinism can reach their full potential, free from prejudice and life-threatening skin disease risks.

Children with Albinism: Protection Begins Early

The dermatological trajectory of albinism is set in the earliest years. Photodamage is cumulative, and every sunburn in childhood contributes to the cellular and molecular burden that may manifest years later as actinic keratosis or skin cancer. Childhood is not just a period of vulnerability but a critical window where a well-structured protection system can profoundly influence lifelong outcomes. The role of parents, caregivers, teachers, and volunteers is paramount.

Protection begins with creating a safe environment. In infancy, this means avoiding direct sunlight, using strollers with wide canopies, applying UV filters on car and home windows, and selecting soft yet dense clothing that covers arms and legs. As children grow and gain independence, the focus shifts from direct control to education and habit formation. Children should be taught age-appropriately about “sun literacy”: why hats and sunglasses are needed, why sunscreen is applied even on cloudy days, and why playing in the shade is safer. Making these actions routine rather than punitive is a key pedagogical goal.

Dermatology team from Portugal providing surgical care and training to medical students in Mozambique.

Prescription glasses being delivered by the Kanimambo team.

Educational institutions have a special responsibility. Schools and kindergartens should extend safe spaces, which requires teacher awareness of albinism and its risks. Simple measures—allowing hats and sunglasses in class, providing shaded play areas, adjusting outdoor activity schedules to low-UV times, and storing sunscreen for reapplication—can create inclusive, safe environments. Volunteers and NGOs play vital roles in training staff and supplying necessary resources.

Parents should also instill early self-examination habits, turning them into playful or ritualized activities to foster responsibility for one’s body. Strong photoprotection habits formed in childhood become a natural part of identity and the most powerful preventive tool. Investing in a child’s skin protection is therefore a direct investment in a healthy, full, and long life, minimizing severe disease risk in adulthood.

Psychology and Sun Protection Fatigue

The psychological burden of living with albinism, especially the need for constant lifelong sun protection, often remains in the shadow of medical guidance, yet it significantly affects quality of life and adherence to preventive measures.

Sun protection fatigue is a real phenomenon, manifesting as irritation, low mood, or emotional exhaustion from daily planning, remembering, and performing protection routines. It represents chronic stress tied to constant vulnerability and inability to relax outdoors like peers.

Additionally, stigma and social pressure amplify this burden. Wearing special clothing, wide-brimmed hats, and dark glasses in all weather draws attention, questions, teasing, or social exclusion, especially during adolescence. In some cultures, stigma is extreme and life-threatening. Even in more tolerant societies, internalized feelings of being “different” can be challenging.

Psychological support should be an integral part of comprehensive care. It is important to normalize feelings of fatigue, sadness, or frustration. Support can take multiple forms: individual or group therapy for safely expressing emotions; participation in communities of people with albinism for mutual support; counseling for families to balance necessary protection with fostering independence and self-confidence.

Acknowledging and legitimizing the psychological aspects of albinism is as important as medical care. This allows individuals not only to care for their skin but also to maintain mental well-being, building resilience and accepting their uniqueness as part of their identity rather than a limiting factor.

Conclusion: A Living Checklist for a Full Life with Albinism

Albinism is a genetic fact, not a sentence to inevitable severe skin consequences. Modern knowledge clearly shows that tragic statistics of skin cancer incidence and mortality, especially in high-UV regions, are primarily the result of information gaps, lack of resources, and systemic support. Most consequences are preventable. Transitioning from passive vulnerability to active risk management is possible and based on clear, actionable principles.

A practical path to safety can be viewed as a living action algorithm integrated into daily life:

- Uncompromising photoprotection as the foundation. Consistent use of broad-spectrum SPF 50+ sunscreen, protective clothing with UPF, wide-brimmed hats, quality sunglasses, and planning activities according to the UV Index.

- Vigilant skin monitoring. Monthly self-examination following a clear routine, maintaining a photo archive to track changes, and cultivating the habit of noticing new or changing lesions.

- Utilizing modern tools. Incorporating digital assistants for UV Index monitoring, safe sun exposure timing, and preliminary assessment of suspicious skin changes, adding objectivity and discipline to self-monitoring.

- Timely consultation with a specialist. Building a long-term partnership with a dermatologist and seeking immediate consultation for any concerning signals, without a wait-and-see approach.

Combined with community support and attention to psychological well-being, these steps transform albinism from a constant threat into a manageable condition, with understood and minimized risks. Knowledge, prevention, and technology together provide not just safety but the opportunity to live a full, active, and free life, no longer overshadowed by fear.

“I Want to Love the Sun”: Kato’s Difficult Story

Emin, tell us about the day Kato was born.

My wife Naomi was screaming in pain. And when it was all over and the midwife brought him out—there was silence. He was white as milk, with white hair and pink skin. The midwife recoiled. She dropped him on the bed without touching him. She only said, “Zeru zeru.” Ghost. Spirit. Then she said, “He cannot stay here.” When I came to myself, I was scared. We were all scared.

How did your family’s life change after that?

My wife stopped going to the market. Neighbors avoided our house. Children shouted “mzee!” (white) and threw stones at the roof. Working in the fields became impossible—who could we leave him with? The sun would burn him in ten minutes. We hid him indoors during the day. Like a little chick.

Describe a normal day when Kato is out in the sun. What happens?

First, his skin turns red. Quickly, like he’s been hit. Then he starts crying from the burning. By evening, blisters appear filled with fluid. They burst, and the skin peels off in sheets. Underneath, it’s pink and raw, like a newborn’s. He can’t sleep. Any contact with the sheet hurts. We put wet cloths on it, but it barely helps. After a few days, a dark, hard patch remains. It doesn’t go away. He already has many on his hands and neck.

And what about his eyes? Does he complain?

Constantly. Even inside the hut, if he looks at a crack in the door, he squints and says it “stings like needles.” Outside, without glasses, tears and pain immediately. He rubs his eyes with his fists. The mission gave us glasses once, but they’re big and always slip off. When he doesn’t wear them, his eyes are red, like he hasn’t slept for a week.

What’s the hardest part of everyday life right now?

The sun. Always the sun. No clouds means Kato stays in a dark room today. Again. He’s seven. He wants to run. But even in the shade—after an hour he’s already burning. Reflected light from the sand also burns. We have to warn him about the sun, that it will hurt again.

And the skin, these hard patches? What do you do?

What can we do? Cream runs out. Sometimes donors bring some, sometimes not. These patches on his hands, on his forehead… they’re rough, sometimes crack, and ooze. My wife rubs them with palm oil to soften them a bit. The old woman says it’s because he’s not human, that spirits leave marks on him. I know it’s from the sun. But the doctor is three days away. No money. No time. And the sun. Of course, we’re afraid that one of these sores will start growing, like a fungus. This happened to our neighbor’s son… he died on the way to the hospital.

Emin, have you heard of technologies that could help? Like a phone that can assess risk from a photo?

Are you serious? We don’t have a phone with that kind of camera. We don’t even have electricity to charge it. That’s talk for people in the city. For white people. Our reality is heat, dust, and fear that this hard patch on his ear will turn into something terrible. And we wouldn’t even know in time.

How do you cope? Do you have a routine?

Before ten in the morning and after four—that’s his time, if absolutely necessary. Volunteers taught us. He wears my long-sleeved shirt and a hat, we put on what’s left of the cream on his face and hands. He moves quickly, doesn’t look around. In the middle of the day—never. That’s the rule.

What gives you hope?

He does. He learned to read before he could walk in the sun. Sometimes he says, “Dad, in this book people fly in machines. I’ll build one with a roof.” He dreams of a roof. And of loving the sun. When it rains and clouds cover the sky—those are our holidays. He can go outside, look at everything: the birds, the wheel, the green grass. He absorbs it all. On those days, he’s happy, because he can see as much as he wants.

Your main dream for Kato?

That he lives. Just lives. That fear doesn’t eat his future. That people see him as a human, not as a sign. That’s all. And that he always has a roof over his head. For his whole life.

Image credit: Photos are provided by Kanimambo – Association for the Support of Albinism.